The Peninsula

All Eyes on Chinese Trade with North Korea, But There is a Problem

By William Brown

China surprised many Washington pundits by signing on in February to what looks like fairly tough trade sanctions on North Korea. Most importantly, it agreed to put a halt to its purchases of coal and metal ores to the extent that these provide foreign exchange to North Korea’s military and to the nuclear and missile programs. The move is significant because anthracite coal exports have long been a staple in Pyongyang’s export mix, earning over $1 billion last year in sales to China, and much of these seem to be managed by North Korean military units. Other specific prohibitions include Chinese sales of aviation fuel to North Korea, the rationale presumably that all but the smallest North Korean rockets are propelled by a kerosene type fuel imported largely from China or produced domestically using crude oil provided by China. There are lots of loopholes, so all eyes should be on China in the next few months to see if it is meeting the spirit, if not the often ambiguous letters, of these sanctions. As China says, they are not supposed to hurt the livelihood of people, instead aimed simply at convincing Pyongyang to change course on nuclear weapons, or at least come to table to discuss them.

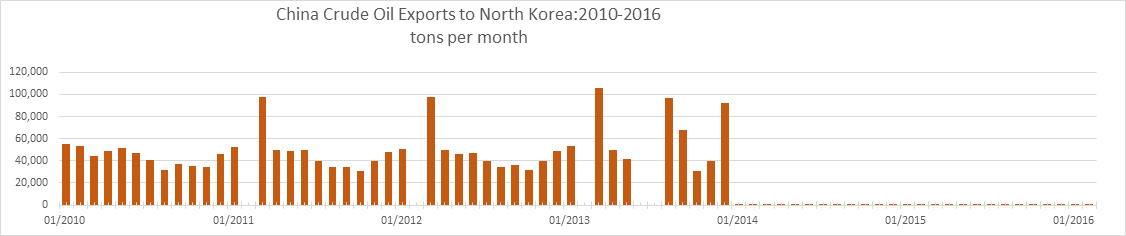

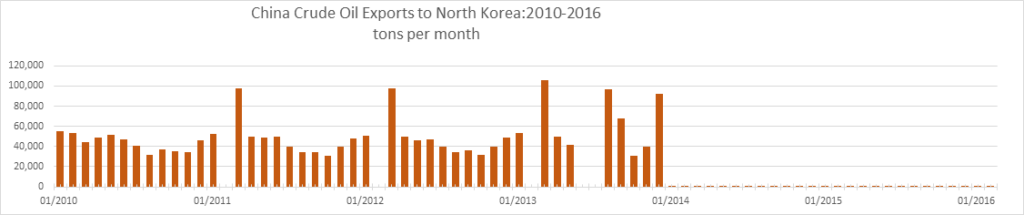

So what should analysts be looking at? China’s Customs Bureau publishes extensive and timely export and import data on its trade with North Korea and this will be the first line in understanding Chinese actions and intentions. But right at the outset there is a big problem. As figure one shows, this official Chinese reporting stream shows a complete halt to Chinese crude oil exports beginning in January 2014 and lasting at least through February 2016. March data will become available in a few weeks. Objective analysis shows clearly that China did not cut off crude exports in 2014 and these numbers are, to put it politely, misleading.

Beijing has provided no explanation for zeroing out reported crude shipments, despite media reports that show they continue as they have for decades. North Korea Daily reporters, for example, have visited the transshipment site on the Chinese side of the border where officials told them crude continues to flow as normal. Commercial imagery also shows the refinery is working and there are no other reasonable sources for the crude feedstock. The crude, about 50,000 tons a month, probably originates in the big Daqing oilfield in Heilongjiang province and travels across the border through a short, 11-mile pipeline, to Ponghua, the country’s only continuously operational refinery. In past years there was an occasional month or two in which no crude was reported but these were always followed by double shipments in later months. The refinery has no seaport although there is a rail connection. North Korea has one other very old refinery, near the Russian border, which is served by a port facility, but it operates rarely with no dedicated source of crude. So if the Chinese data is accurate, North Korea has had no crude oil supply for over two years and has been depending entirely on very modest imports of petroleum products to fuel its entire economy. Clearly this is not the case so there must be something awry with the data. Beijing chooses not to explain this situation and U.S. and other foreign officials, for some reason, have not asked for an explanation, at least not one they have openly reported. In my view this is enough of a problem to question the validity of all Chinese trade with North Korea and thus to question whatever new data shows up in March and April.

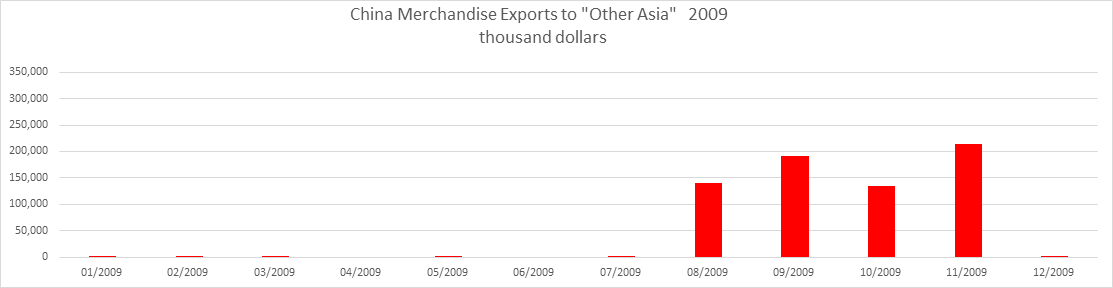

Without what would seem to be an easy Chinese explanation, we are left to speculate. A likely hint is provided by a similar occasion in 2009 when Chinese Customs suddenly stopped reporting its usual detailed monthly trade data for North Korea. The data break lasted for four months, August through November, and was never, in my understanding, explained to users of the Chinese data.

With some effort one can figure out, however, that all of this data–detailed 8-digit Harmonized Code commodity information on exports and imports, volume and value, and prices–were tucked into a rarely used partner category “Other Asia, Not Elsewhere Specified” so that the data was never actually lost or misreported. In December figures in that category dropped back to near zero and all of the detailed commodity data showed up again as Chinese trade with North Korea. (The above graphic only shows the aggregate but details tell the same story.)

Although not conducive to building confidence in Chinese statistical methods, this procedure at least did not distort China’s overall trade with the world. A Chinese official whom I queried said simply that Pyongyang probably complained that China was revealing state secrets in reporting the bilateral data so for a few months Beijing acquiesced. Later, and after I asked the question, the Chinese must have thought better of it and again publish the data with North Korea as the trade partner.

I have searched at length to find another place in the Chinese data where the crude oil shipments to North Korea now could be hidden in the same way and perhaps for a similar diplomatic reason, but cannot find it. China is a net importer of crude oil but it exports occasionally to Japan and other countries. The country’s total crude oil exports are now apparently distorted by the absence of the North Korea data. Does this omission also reduce China’s overall commodity export figure, or even its GDP calculation? At about $150 million a quarter, this would have only a tiny 0.1 percent negative impact on quarterly GDP, but again why would Beijing mess up its data in this way.

Analysts speculate that China may have suddenly put the trade “off books” or that they now account for it as an aid shipment. But either clearly would distort Chinese data in ways that should bring more skeptical attention to its entire economic data reporting scheme. After all, if a political decision can alter data with North Korea, why can’t balance of payments or GDP numbers be similarly distorted by the whims of the politburo? The crude oil has most likely always been an aid shipment—an (eternal) gift from the people of China to the DPRK as offered by Chairman Mao in the 1960s—but that doesn’t mean it should not be accounted as an export. Proper double entry accounting means it should be an export commodity in the trade account offset by a negative in the remittances line in the current account, or, if the commodity is paid for by a long-term zero or low interest loan, it should be offset by a negative (outflow) in the capital account. Presumably, China’s National Bureau of Statistics, overseer of Chinese national accounts data, is making this adjustment; that is, it is making a change to the foreign aid or the external credit line, but this would mean it is probably distorting information on Chinese foreign aid and national oil production and consumption, needlessly confusing users of its data by such “off-books” accounting.

The only legitimate reason for excluding Chinese crude oil shipments from its Customs data that I can think of would be if China had changed its pattern and is now transshipping third party crude oil to North Korea, possible since China is a large net oil importer anyway. But given there is no port facility at Ponghua, this would lead to the seemingly absurd situation where the imported crude would have to travel inland to the transfer facility and then onward to North Korea. And again, if this is the case, why not announce it?

The aviation fuel issue is interesting as well but the sanction here is less than meets the eye. China exports a variety of petroleum products to North Korea, probably mostly on commercial rather than long-term aid program terms, and in low volumes compared to the crude oil. These alternate between gasoline, light diesel, and kerosene or “jet fuel” products. A significant volume of jet fuel is reported to have been provided in 2014 but essentially none since then, while shipments of diesel and gasoline have increased. But clearly this is not all of North Korea’s aviation fuel requirement. Jet fuel or aviation gasoline can easily be produced from the crude oil provided to the Ponghua refinery so more diesel imports mean the refinery can shift from diesel production to jet fuel production.

These data issues are not meant to question China’s North Korea policy. I for one think China has acted fairly reasonably with its troublesome neighbor and long-time ally. We do not give it much credit, for example, for not shipping military equipment to Pyongyang for more two decades, watching Pyongyang’s stock of everything from jet fighters, to radar systems, to ground equipment deteriorate and fall into obsolesce. If we are not careful, China could do a lot to make Pyongyang happy, for example in air defense, that would upset our military posture in South Korea. Moreover, its trade with North Korea is nearly balanced–aside from the crude oil and assuming we can trust the rest of the data–suggesting it is providing little aid or investment credit. And to the extent that China-North Korea trade is doing fairly well, it is in product lines that seem to be helping a market economy develop in North Korea, such as textiles. But without public explanation of the crude oil shipments, or better, a return to full reporting of these shipments, confidence in Beijing’s North Korea policy and indeed the transparency of all its economic data will be lacking. And whether or not Pyongyang thinks it is a state secret, China’s public deserves to know what it is giving to North Korea.

So, if the data for March and April on Chinese coal and ore imports from North Korea suddenly turn to zero, will we trust that is indeed the case?

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from Joseph’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.