The Peninsula

Asia’s Latent Nuclear Powers: A Review

By Troy Stangarone

Should South Korea develop a nuclear weapon to deter North Korea? Should Japan go nuclear as well? These questions have been asked since North Korea conducted its fourth nuclear test earlier this year and Donald Trump suggested that both countries might need to eventually develop their own nuclear deterrents. While much of this discussion has been superficial, in an important and timely new book, non-proliferation expert and International Institute for Strategic Studies Washington, DC office head, Mark Fitzpatrick, explores Asia’s latent nuclear powers and the prospects of South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan going nuclear.

At a time when North Korea’s drive for a deliverable nuclear weapon has South Korea debating its options for its own device, Fitzpatrick’s “Asia’s Latent Nuclear Powers: Japan, South Korea and Taiwan,” explores important issues related to why South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan might decide to one day pursue a nuclear option, how quickly they could do so, and what constraints the would face, but perhaps most importantly why all three have refrained from developing nuclear weapons in the face of a nuclear-armed China and North Korea.

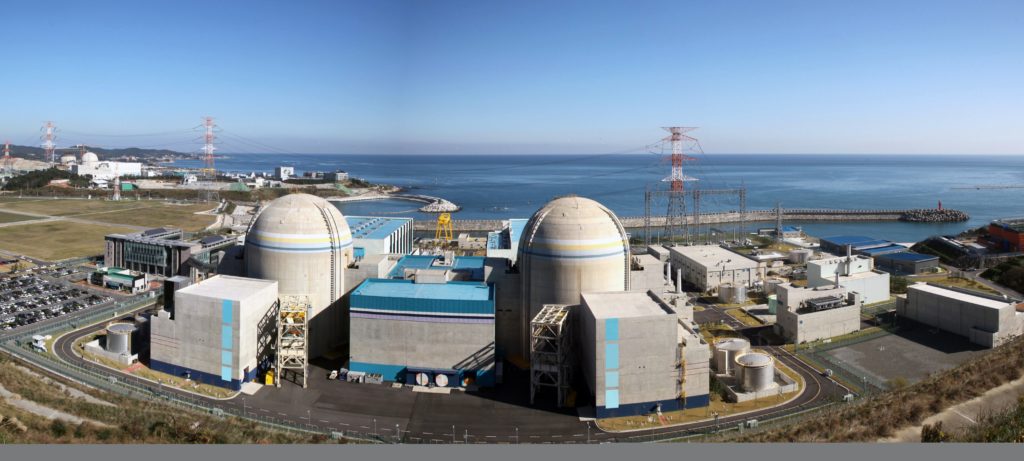

While South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan are not nuclear weapons states, their advanced civilian nuclear power programs give all three the potential to develop nuclear weapons more quickly than other states in the region. This advanced stage of nuclear development and restraint from the development of nuclear weapons, makes each of them as Fitzpatrick notes, latent nuclear powers.

In the case of each, there is also a history of prior pursuit of nuclear weapons. In South Korea’s case, the motivations for its initial pursuit of nuclear weapons perhaps also suggests why Seoul, or Japan and Taiwan, might consider going nuclear in the future. At the time, North Korea held a military and economic advantage over South Korea, and U.S. responses to increasing North Korean provocations raised concerns about the credibility of U.S. security assurances. This concern was only heightened in the late 60s when President Nixon unexpectedly announced the U.S. intention to shift conventional defense in Asia to its allies, the withdrawal of the Seventh Infantry Division over South Korean objections, and the U.S. normalization of relations with China.

For those who would question whether the United States should continue to provide extended deterrence to South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, Fitzpatrick’s study will prove illuminating. In the absence of U.S. security guarantees, South Korea would face a nuclear-armed North Korea. Japan would face both a nuclear-armed North Korea and China. While Taiwan would face a nuclear-armed China that continues to modernize its conventional forces, forces which it might not be able to deter without U.S. assistance. The decision of say, Japan to go nuclear would likely trigger a similar decision in South Korea. It is the U.S. security presence and assurances of extended deterrence, Fitzpatrick argues, which has played an important role in the decision not to pursue nuclear weapons.

One important takeaway from Fitzpatrick’s work is that going nuclear would not be as easy for South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan as is generally presumed. Even for advanced nuclear programs such as those in South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan, developing a nuclear weapon would take time and entail significant economic and security costs for each. It is these costs, which are rarely discussed, that help make the nuclear option so unappealing under the current security environment.

For anyone who wishes to understand why Asia’s latent nuclear powers have remained so and what might trigger a change in their posture, Fitzpatrick’s work is an important piece of scholarship.

Troy Stangarone is the Senior Director for Congressional Affairs and Trade at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are his own.

Photo from IAEA Imagebank’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.