The Peninsula

South Korea’s June 9 Surprise: Economic History Worth Replicating in North Korea

By William Brown

September, 1961 was not a happy time in South Korea, at least according to the US Intelligence Community. See how CIA described the dismal situation soon after junta commander Park Chung-hee’s coup d’état, in a declassified National Intelligence Estimate.

“The greatest threat to South Korea, at least in the near term, comes from within South Korea. The country lacks a sense of national purpose and faces both tremendous economic problems and a brittle political situation. The military junta seeks to provide the drive and stability which was lacking in the previous civilian government but is subject to internal factionalism and lacks general public support in confronting these enormous problems. … U.S. aid will probably succeed in preventing economic collapse. However, even under the most favorable circumstances, progress will be slow and South Korea will continue to require large-scale foreign aid for the indefinite future if it is to remain an independent nation allied with the West.”[i]

The longer-term threat was North Korea, seen then as a vibrant economic entity, pulling the frustrated South into the communist orbit.

“One thing seems fairly clear; both the South Korean people and the leadership face many disappointments, frustrations, and failures in the years ahead. In such a situation, the desire for economic progress and for an end to hopeless temporizing, rising interest in unification, and continued enticements offered by the [more prosperous] North Korean regime could lead to some movement in the south toward an accommodation with the north.”

National Intelligence Estimate 14-2/42-61, 12 September, 1961.[ii]

Within months, South Korea had set forth on what now must be seen as one of the world’s most remarkable economic and political development paths. And within about a dozen years, North Korea would default on foreign credits and begin a long decline into famine.

Not known for its prescience in such matters—just eleven years earlier the brand new CIA had boldly said China would not enter the then flaming Korean War[iii] — this pessimistic Estimate may have served as a useful warning to the Kennedy Administration which went on to put some of its best minds together to change the nature of U.S. assistance to Seoul. Instead of commodities aid—free food—that was ruining South Korean agriculture, the aid program focused on fixing the overvalued monetary system and developing exports. Who did this and why would be a good topic for historians to revisit and our countries to honor. But I’d like to look at the take-off from the perspective of peering back into the past with an eye toward the future. How did this intelligence forecast turn out so incredibly wrong, and wonderfully so? And what can we learn in order to convince North Korea to make a similar about-face.

An excellent new book, The Korean Economy: From a Miraculous Past to a Sustainable Future, by Eichengreen, Lim, Park, and Perkins[iv], provides what is probably the school view of South Korea’s remarkable turnaround. In looking for an up-to-date book for my Georgetown University course on the two Korean economies, I was pleased to discover this work, not the least because it includes a chapter on North Korea. But I must say I was disappointed in reading what it has to say about what caused the economic take-off. This is not to say that they might not be right; it just doesn’t fit with my pre-conception and I’d like to see a new, more full, academic discussion. Perhaps objective economists in South Korea, that is academics not predisposed to punish Park for his authoritarian rule, can help with this.

At its essence this is a chicken and egg discussion. Eichengreen and others say that it was Park’s shifting the economy from import substitution to export-led industry that allowed savings and investment to blossom, raising the productivity of Korean workers. Exports, from a subsistence-level economy, were possible only because foreign aid provided the surplus needed to attract investment. The pull from abroad thus lifted the economy.

In contrast, I have thought it was reforms to the money and banking system that provided incentives to save, even out of very low incomes, that created an exportable surplus which then pulled in the foreign investment that jump-started the economy. In other words, an outward push from inside Korea provided the lift. Foreign aid was less important. An arcane, perhaps, but I think important distinction, especially as we look towards North Korea’s current predicament and to its penchant for nationalist self-reliance.

My view stems from a personal memory—admittedly a dangerous source of analytical vigor. I was a young American boy living in Kwangju, capital of South Chulla province, during this time—fortunately, my Presbyterian missionary parents had not read the secret CIA document. Early one rainy season morning in 1962, my mother got me up to search our neighboring American doctor’s house for a stash of hwan cash. The doctor and his family were away but had rung up (that is the way the old phone system worked) to say he had a bunch of South Korean money that needed to be turned in; he just couldn’t remember exactly where it was, probably in his library. Exciting in a way I’ll never forget, I found the stash of cash, in cut-away books just like you see in spy novels. The bigger story, of course, and unknown to us at the time, was the change to the monetary system and to Korea’s economy that this currency reform signaled. The initial phase was not completely successful; apparently not enough new won notes had been secretly printed in England and brought by ship to Korea, but within months the new cash had taken hold. So if I was to make a point estimate, June 9, 1962 was the day that made modern South Korea. It should be a holiday. Everyone was given a few days to take their hwan money, at least up to a pretty high limit, and go down to the Cheil bank and exchange it for newly printed won notes at a 10-to-one ratio; after that hwan would be useless. Larger amounts of money had to be deposited for a year at a high interest rate but most of the hwan was converted and prices changed accordingly. And to encourage the public to deposit and save their new won, something like 20 percent annual interest rates were offered. Even in days before calculators, I remember figuring out how fast the money would grow and how soon I could be a millionaire—forgetting the problem of inflation that this new policy was meant to address.

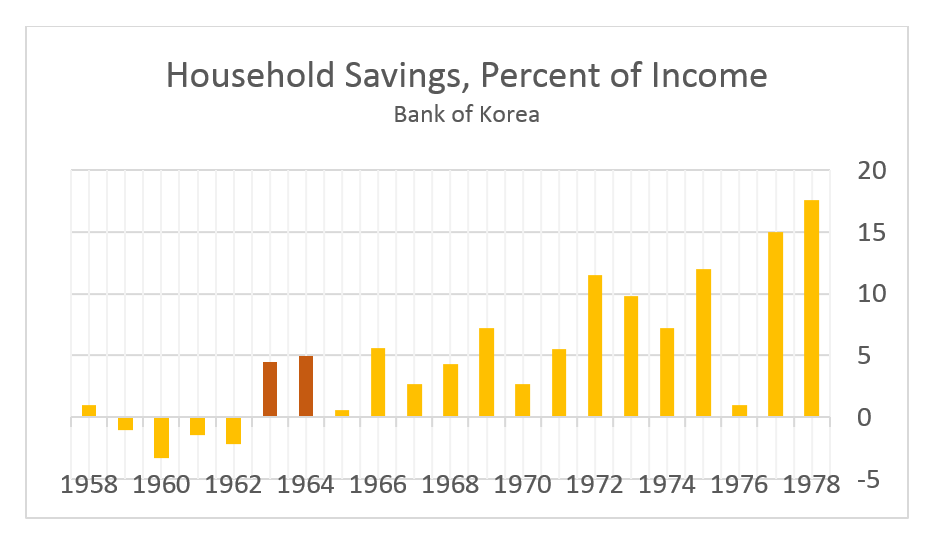

I wasn’t the only one thinking this way and very quickly South Koreans shifted from being just about the worst savers in the world to being the best. Poor people stopped spending on weddings and funerals and instead saved money, and the banks used these saved resources to lend to farmers to buy small tractors, assembled from kits made in Japan, revolutionizing agricultural productivity.

Elimination of U.S. food aid, and government support to higher agricultural prices, as well as subsequent deals with Japan and the World Bank helped, but the driving force was a decent money and banking system that gave the right incentives to the Korean public to save and invest in the future. At least that is the way I have remembered and taught the story.

Eichengreen and the other authors, however, use the data to paint a slightly different picture.

“Domestic savings remained in the single digits (share of GDP) in the first half of the 1960s, the takeoff period. … The most dramatic change was, in fact, the rapid growth in exports. Exports at constant prices grew by 35 percent per annum from the end of 1963 to the end of 1969.[v]

The data shown in their text, however, are at five-year intervals so I question the interpretation of the leads and the lags. Looking at annual household savings data, (graphic below) it seems that the savings growth kicked-in in 1962 and 1963, simultaneously with the money change and a year before exports began their upward spiral from a tiny base.[vi] Admittedly 5 percent household savings are not much but it is the change from nothing that arguably sparked Korea’s real revolution.

As I say, a chicken and eggs argument. If my memory serves, it was human hair (wigs), plywood, and leather goods that started the export push, not products that required foreign investment. But clearly Eichengreen is right about what happens next; general and soon-to-be “president for life” Park got on the export bandwagon and the rest is history. Export growth soared giving the economy a huge boost even as savings and investment rates rose, allowing the import of capital goods for South Korean industry. Park’s most controversial policy was then to shift from light industrial exports, especially textiles and footwear, to heavy and chemical industry, despite what appeared to World Bank and U.S. economists as a comparative advantage in labor intensive products. By now it would be hard to argue that Park wasn’t correct but, whatever the case, on the basis of this surge in investment, South Korea’s comparative advantage has shifted, for the time being, to heavy industry. I say for the time being since China looms as a tough competitor in all of these products and is investing even more heavily than did Korea. Another important step, as is hinted at in the old NIE, was Park’s creation of an objective and expert Economic Planning Board that supervised the creation and publication of data that his and subsequent governments could use as the road map and guide for economic policy making (and which makes possible our current analysis of what caused the economic takeoff). The U.S. role was critical as well. Despite missteps with respect to aid, the U.S., soon after liberation from Japan, had supervised the fundamental change in Korea from a tenant based agricultural economy to a capitalist one with massive land reform giving land to the tenants, and, of course, by providing the security shield that protected the country from the Communists. While initially skeptical of the currency reform—U.S. officials had not been notified in advance even though the U.S. was financing about half of the South Korean budget—U.S. balance of payments support that followed allowed the new won to achieve credibility.

But the real genius of the Park administration, it seems to me, was those early courageous and risky steps in changing the money and using the change to create a sound currency and a high-interest banking system that encouraged savings and that recognized the high returns on capital if used only in high productivity endeavors. Now seen as a textbook solution to be sure but one that must have been complicated and risky for the generals to manage. Subsequent Seoul governments have relied too much on banking and not enough on more efficient direct capital markets—stocks and bonds—but all of that is a different story, well told in Eichengreen.

The parallels to North Korea today are interesting and I would hope officials and scholars in Pyongyang are carefully studying Park’s success. I say carefully since they tried something similar to the South Korean currency reform in 2009 but bungled it badly. On paper what is known as the 2009 currency redenomination must have looked similar but with critical differences. Citizens were told to change about a third of their cash into a redenominated currency of the same name at a 100-1 ratio. That ratio doesn’t matter but the fact that only a small share of cash could be converted, and the absence of a name change, are important. North Koreans immediately saw most of their money devalued by 99 percent over the span of a few days and naturally associate that disaster with the North Korean won notes. It isn’t clear what was supposed to happen with their bank accounts but these were artificial anyway since cash can’t be withdrawn from a bank except with special permission—maybe like a 401k that never matures—and that policy has not changed. By sharply reducing the money supply, the move might have been designed to bring black market prices down close to the fixed ration price levels and end the arbitrage that was and continues to destroy the planned, fixed price, economy. That didn’t work since market prices immediately soared, leading to an even larger gap between official and market prices.

Whatever the reasons for the redenomination, it backfired—even strongly socialist PRC commentators called this a theft of the people’s money. The Kim Jong-il government executed the party finance chief and, a first, offered an apology to the public. But once done such a deal cannot be undone and North Korean won quickly became essentially worthless, with foreign money, U.S. dollars and RMB, seeping into the circulation in large amounts. Pyongyang by now has stabilized the won at prices significantly above the pre-2009 level but the foreign money circulates without impediment, an astonishing development in a so-called Marxist and “self-reliant” economy. To hire a taxi, you now need something like two U.S. dollars. To buy an apartment, you need $30,000 US.

In these respects, the situation now is probably not so different than South Korea in 1961. At least a market now exists and the command economy seems to have lost some of its sting. Entrepreneurs make dollars buying and selling in the street markets, and former (maybe current) officials and military officers might be hoping to make it big, using their government connections and licensing abilities to make millions of dollars by building apartment buildings and selling the flats, carefully keeping enough dollar cash handy to pay off the authorities.

In fact, it is interesting to think that the 1961 NIE might work well today, simply exchanging “North” for “South” Korea. Land reform that gives farmers’ ownership rights; stopping the inflow of disrupting foreign aid that discourages export development; and an export push all are within the capabilities of even a sanction-limited Pyongyang government. But most important is creating a money and banking system that allows the North Korean people to do their own saving and investing. If Kim Jong-un wanted to link such a policy to his grandfather, all of this could be placed in a “juche” nationalist and self-reliance context. Clearly, against the advice of many non-Koreans, Park Chung- hee managed to change South Korea from a beggar, aid-dependent country to a self-reliant lending and aid giving powerful and well-liked country. One would think the young Kim would like to do the same. But before any of this can work, he needs to fix his rapidly dollarizing monetary system and adopt capitalist tools to raise savings and create private incentives to invest in the future. A decent bank and a decently positive real interest rate would do wonders. And like Park, Kim might be able to use a little American and Japanese help to get this done.

So, where is the briefing book that we can give the young General that will properly explain what he needs to do? I’m pretty sure the junta leader’s daughter can give the lecture.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photos courtesy of the author.

[i] http://www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/document_conversions/89801/DOC_0000661631.pdf

[ii] ibid

[iv] Barry Eichengreen, Wonhyuk Lim, Yung Chul Park, Dwight Perkins; The Korean Economy: From a Miraculous Past to a Sustainable Future, Harvard Press, 2015

[v] Ibid. p. 64.

[vi] http://kosis.kr/eng/statisticsList/statisticsList_01List.jsp?vwcd=MT_ETITLE&parentId=L#SubCont