The Peninsula

New Year’s 2017 in Pyongyang: Self-Reliance by Necessity or Design?

“Previously, all the people used to sing the song We Are the Happiest in the World, feeling optimistic about the future with confidence in the great Comrades Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. I will work with devotion to ensure that the past era does not remain as a moment in history but is re-presented in the present era. On this first morning of the new year I swear to become a true servant loyal to our people who faithfully supports them with a pure conscience.” – Kim Jong-un 2017 New Year Address

By William Brown

Even Kim Jong-un seemed a little melancholy in his New Year’s speech, reflecting perhaps the sad state of international affairs everywhere this winter. He continues to forge ahead, saying he wants to improve both the economy and the nuclear force, something the outgoing U.S. administration says he can’t do. For him the Obama administration’s slow shift—like all previous administrations it began by simply promising North Korea could not have nuclear weapons, and ends with its intelligence chief essentially giving up on denuclearization, while resorting to still more sanctions—would appear to be a victory of sorts, even more since in some ways the economy has improved during Kim’s five-year tenure despite sanctions. Ironically, as growing weakness in his socialist “command” economy gives way to a rise in market activities, mobility and productivity of labor is thriving, pushing out GDP growth at least as measured by South Korea’s Bank of Korea. People now can use taxis when only a few years ago, mobility even by bicycle was frowned upon. And use of money—two U.S. dollar bills for the taxi ride—has devoured the old ration and permit system. Individual incentive would thus seem to be offsetting the continuing drop in foreign trade and investment that the West counted on to stop the nuclear program. But even with this burst in market activity, Kim seemed to apologize for not advancing the economy faster, cognizant no doubt of big troubles in the nation’s dilapidated infrastructure and in the dollarized monetary system which he can’t control. And now, by speaking of the yet incomplete ICBM program, Kim has sparked a new promise from incoming President-elect Trump to stop that program, ensuring the 70-year fight with America will continue.

Disappointingly, Kim’s speech offered nothing in the way of economic reforms that could regularize the market activities that are bringing economic growth and that could launch North Korea on a China reform-type path, but instead he harkened back on an ill-defined “five-year plan,” 70- and 200-day “speed battles” and other socialist rhetoric, not I suspect, what the people wanted to hear. One may ask how long can he get away with this. By not addressing the increasingly obvious contradictions between the socialist and market systems simultaneously at play in the economy, he stokes confusion and eventually, one would expect, social disorder. Market prices and wages are so different from socialist prices and wages that less ideologically pure individuals are becoming rich playing the systems against each other—taking free, state supplied, electricity and selling it from car batteries to charge cell phones—while steadfast state sector employees and complacent farmers, and the loyal military, remain exceedingly poor, stuck to a wage system them gives them almost no money and increasingly sparse rations. Given his speech, it is not clear Kim understands his dangers, both with America and with his people. Or maybe he does hence his mood.

Kim also said little about the country’s abysmal foreign relations, except to emphasize the need for “self-reliance” in the heavily sanctioned country, using less ideologically tainted verbiage than the old “juche” of his father and grandfather, and for eventual unification with South Korea to take place in an “independent way”, meaning, to be sure, that the U.S. must withdraw. Given President Park’s trouble, he might think the time is getting closer. But the people have heard this over-and-over and might be tired of the quixotic politics of their rich southern brothers.

Kim, of course, does not mention the ever-lengthening list of UN sanctions—a new unanimous Security Council Resolution, 2321, was agreed upon on November 30—and U.S. and others added to their bilateral sanctions. And even pundits and former administration experts now say the sanctions are having no impact on Kim’s decision-making. But they are impacting the economy, and the people’s livelihood, a troublesome aspect of the sanctions process that seems not to be well studied. Sanctions can cut off foreign exchange to the government, and limit its ability to procure foreign products and expertise needed for the nuclear and missile programs but, by limiting free market activities, they also can add to the domestic authority of the sanctioned regime and help it control its borders. This later is particularly important when a socialist or partial command economy such as North Korea is involved. Such regimes must prevent foreign buyers and sellers from corrupting and distorting their internal socialist pricing and wage mechanisms or chaos will break out. Economic planners in Pyongyang thus will use foreign imposed sanctions to help control exports and imports in ways that better fit their plan. They may want to stop the export of coal, for instance, to supply more to the overburdened electric power system. Moreover, when quotas are involved, as with the new coal sanctions, valuable licenses can be sold for ready cash by government authorities, absorbing dollars from the emerging private sector. The Iraq “food for oil” UN sanctions of the 1990s stand as a case in point. The program allowed Hussein regime officials to earn billions of dollars of pocket money while gaining socialist control over the country’s large agriculture sector.[1] North Korea’s economy was socialized well prior to sanctions, but we should ask if sanctions are allowing the regime to fend off reforms that collapsed such systems everywhere else in the communist world.

Official trade data from partner countries all over the world makes it clear that whereas Pyongyang’s decision-making may not be being influenced by the sanctions, actual trade, and thus the economy, is by now strongly affected. With the important exception of China, North Korea’s trade relations have by now been shattered, everywhere. Even Russia, which argues in the UN sanctions meetings that the North Korean economy should not be targeted, trades exceedingly little with North Korea, after being its most important partner for decades prior to the demise of the Soviet Union. Only three years ago, it announced with great fanfare the resolution of a $10 billion debt overhang and billions of dollars in proposed investments in the rail and mining sectors. Russian two-way trade with North Korea through October 2016 amounted to only $60 million, and $40 million of that appears to be transshipments of Russian bituminous coal to South Korea and China via the ice-free Najin-Sonbong port, using a newly refurbished rail link to Vladivostok. Indian and Thai trade also fell off sharply through the first three quarters. European trade has gradually shrunk to near nothing–$23 million in two way trade over the January to September period, joining Japan, South Korea and the U.S. with virtually no commercial relationships with North Korea. In 2016, it seems likely that Philippines was the only country in the world to significantly increase its North Korea trade.

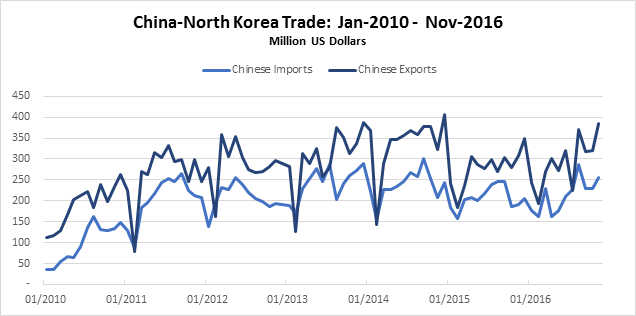

China, of course, remains the outlier as might be expected given its long border with North Korea and its history of protection of the regime. November data show trade continued to climb even after the “strongest ever sanctions” in April, largely due to a big jump in North Korean coal prices. The issues with Chinese implementation of sanctions may now crystalize as misunderstandings regarding the April sanctions appear to have been straightened out in the November 30 rulings. Most importantly, Beijing accepted strong limits on imports of anthracite coal, Pyongyang’s largest foreign exchange earner. For the month of December 2016, the Security Council allowed North Korea to export–China to import since there are no other buyers–one million tons with a value of up to $53 million dollars. This would be about half the value and volume of previous months in 2015 and 2016. (In comparison, Chinese data for November released a few weeks later, showed imports of 1.9 million tons worth $139 million, a jump from October since prices rose from $55 to $73 a ton, and volume rose from 1.8 million tons.) For 2017, annual limits are set at 7.5 million tons and $401 million dollars, whichever is smaller, and represent a big cutback from about 21 million tons likely shipped in 2016 valued at about $1.1 billion. Given the recent rise in prices, and higher capacity, the loss in foreign exchange earnings to Pyongyang in 2017 would be upwards of a billion dollars. Since the country has virtually no international credit, if not offset by exports of other products, this would mean its worldwide imports would need to fall by an equivalent amount.

Within weeks we will see what Chinese Customs has to say about the December imports and if the letter of the sanctions rules are being accepted. Whereas Chinese officials seem to be highly proficient and rule oriented, their behavior in not reporting the far most important trade item—Chinese shipments of crude oil to North Korea apparently provided at no cost—raises important questions. (The graphic above adds to the official data an estimate of the value of these Chinese crude oil exports of about $50 million a month in 2014 and $33 million a month since then.) But these questions also go to some of the core difficulties of sanctions implementation. Will China focus on individual North Korean shippers or the Chinese buyers, giving or selling the latter licenses to import the coal? And on the North Korean side, who and how will decisions be made as to which production units can make the sales? If Pyongyang can exert monopoly power over its exporters, as seems likely, it can raise the price further so that it can maximize profits on the smaller volume of coal that it ships. Any exporter that makes it in under the Chinese quota will thus gain higher profits and more foreign exchange than without sanctions. There seems to be no way to prevent North Korean trade officials from allowing their favorite entities to export the coal, and we might surmise that these are more than likely to be military or state run mines, who will reap more profits, not less. Private or less protected coal mines, or coal siphoned off from the state’s electric power system, will likely take hits.

An unscientific task, to be sure, but if we try to count winners and losers of the new coal sanctions, the ledger might look something like this. A more careful study needs to take place if these sanctions are truly to be applied in a “smart” way.

Winners

- North Korea’s thermal electric power sector (under socialist pricing, electric power is virtually free and power plants are allocated nearly free coal by the plan.) Mines thus try to export coal to earn foreign exchange rather than fill plans, but with sanctions this will be difficult.

- Central planners and traditional socialists in Pyongyang will clearly like foreign sanctions since they will help control the domestic allocation of coal per the plan, and energy use more generally. Foreign sanctions are thus the equivalent of a double-sided wall. Authorities on the North Korean side work to prevent trades while authorities on the Chinese side do the same.

- North Korea’s state and military coal mines, or any units that are privileged by the government’s licensing system, will be able to raise export prices, and garner higher profits. It would not be surprising to see scientific units with their own coal mines gain, not lose, from the sanctions.

- North Korean household users of anthracite coal since more coal will be available at lower cost.

- Regime authorities who accrue coal export licensing powers that can be sold internally. To the degree that Pyongyang already holds monopoly powers, this will not be applicable.

- The Chinese government which likewise can sell import licenses or raise tariff revenue. And Chinese coal producers will be winners since with less competition they can raise prices.

Losers

- Marginal and private North Korean coal mines, and their workforces, who are unable for financial or political reasons to obtain export licenses and will thus be forced to reduce output and sell it to the less lucrative domestic market. Layoffs of miners would seem likely.

- Private sector entities that support these mines and that benefit from the funds that circulate from their generally market based earnings.

- Chinese customers of North Korean anthracite who will face higher prices or tariffs.

- Bureaucracies, and thus the public, in both North Korea and China may well be corrupted by the licensing process.

At first blush it does not seem these will add pressure on Kim to denuclearize, and might do just the opposite–reward an inefficient socialist system while penalizing an emerging, market based system. They may raise the costs and perhaps slow the development of nuclear weapons, but also may add to the regime’s sense of domestic control, and thus raise the benefits of the nuclear weapons program as well—much like a “poison pill” saves a company from an unwanted take-over. But with some changes—for example if Beijing only allowed imports from private-like coal mines, or mines that paid market wages, or mines that had limited access to the government—the incentive structure might be reversed putting more pressure on the regime to come to the table. After all, the poison bottle might spill over and Kim would have to react, maybe by next year’s New Year’s speech. But a least as of this current reading, such changes do not yet seem likely.

William Brown is an Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from (stephan)’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[1] The program allowed Iraq to export crude oil but forced the dollars earned to only be used to import food and medicines. The regime sold licenses for these activities which gave it funds to illicitly import weapons and to provide pocket money for officials and to corrupt foreign organizations, including the UN itself. The program, moreover, was devastating to Iraqi farmers who not only could not import needed fertilizers and farm equipment but who had to compete with virtually free grain coming in from abroad. Hussein took advantage to socialize farming and by controlling food, the sanctions helped him control the country. See: http://www.cfr.org/iraq/iraq-oil-food-scandal/p7631#p6