The Peninsula

Moon Jae-in’s Economic Agenda Three Months In

By Kyle Ferrier

More than any other issue, Moon Jae-in’s platform of economic reform propelled him to the presidency on May 9. While he may have only mustered 41 percent of the vote, President Moon’s consistently high approval ratings — reaching a record 83 percent back in mid-June before coming down to 74 percent in late July — have granted the administration a great deal of leeway to shape the economy. As this week marks the end of his first three months in office, what does the administration’s economic agenda look like so far and how is it being received?

President Moon’s economic plan has come to be known as “J-nomics”, a play on Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s plan to revitalize the Japanese economy, Abenomics. Like Abenomics, J-nomics has three pillars: job creation led by the public sector, expansion of the social safety net with a particular focus on unemployed youth and retirees, and the reform of large multinational Korean corporations known as chaebol. These policies are representative of Moon’s fundamental shift in thinking from his predecessors that helped him win the election. Whereas Park Geun-hye and Lee Myung-bak embraced the idea that jobs were created as a result of growth, Moon has inverted this causal relationship, reaffirming his longstanding preference for “income-led growth” in a speech given to the National Assembly on June 12.

The administration’s Policy Roadmap released on July 19 has provided greater detail as to how specifically it will implement J-nomics. The document includes a number of provisions relating to the three pillars of Moon’s economic agenda. On the first, the policy roadmap states 810,000 public sector jobs will be created, promises to “comprehensively resolve the problem of irregular workers,” and outlines provisions to increase the employment of young adults in the public and private sectors. On the second, the document details expanded welfare programs for unemployed youth, children, artists, dementia patients as well as programs to increase public housing, reform public education and the national pension system, and create a better work-life balance for Koreans, who are among the top three OECD countries for total hours worked per year. On the third, the government pledged to increase minority shareholders’ rights to make chaebol more accountable to investors. It also included promises to foster small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) growth, such as doubling R&D in SMEs by the end of the administration’s term.

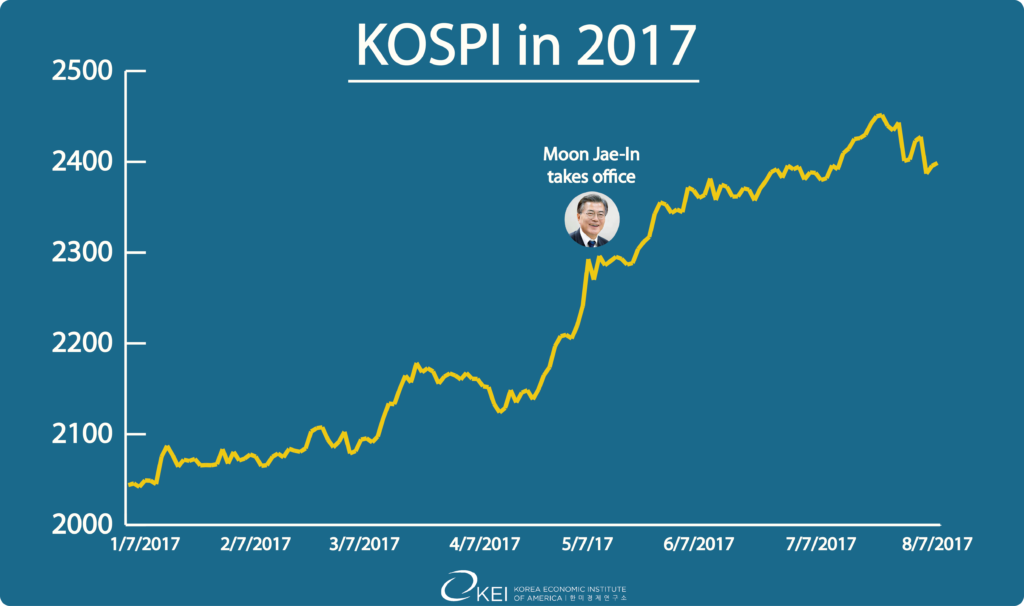

Moon and his team have already begun to implement some of these policies as well others in the same vein. Last month the National Assembly passed an almost $10 billion supplementary budget to support the creation of 2,575 public-sector jobs. The administration has also laid the groundwork for following through on campaign promises to raise the minimum wage to 10,000 won (just under $9) an hour by 2020 by negotiating an increase in the current minimum wage of 6,470 won to 7,530 won in 2018. Additionally, Moon has taken less costly measures to pursue economic policy objectives, such as implementing blind hiring for all public-sector recruitment to make hiring fairer and taking time off to set an example of the importance of a better work-life balance. However, in order to pay for the expansion of welfare programs and government jobs, the administration has also proposed a new tax plan that would raise income taxes on the wealthy as well as raise the corporate tax rate for chaebols from 22 to 25 percent, effectively reversing President Lee Myung-bak’s cut in 2009. Even though the plan would first need to be passed in the National Assembly before it could be implemented, the KOSPI closed 1.7 percent lower last Thursday in response to its release. This comes amidst other anxieties and criticisms of Moon’s economic policies.

To pay for the “income-led growth” agenda, the government will likely need to raise 178 trillion won ($157 billion) over the next five years, though some experts have claimed the new tax plan would not be nearly enough to cover the costs of new programs.

Critics of J-nomics warn of the pitfalls of populism, citing concerns over the government’s heightened involvement in markets and onerous debts. How the administration is addressing household debt is perhaps one of the best examples so far of its mix of market intervention and social spending to tackle an issue. Korean household debt is 92.8 percent of GDP, well above what international organizations deem as critical levels, and is not only a drag on consumption, but is perhaps one of the most significant risks facing the economy. Pressure to resolve this issue is mounting as rising inflation could force the Bank of Korea(BOK) to raise interest rates, which would only exacerbate the problem. The government has taken both top-down and bottom-up measures towards the problem, trying to control rising housing costs by targeting speculators through measures such as increasing capital gains taxes and tightening loan regulations as well as enacting a debt write off program amounting to 25 trillion won($22.3 billion) for 2 million people. Both programs have been met with a mixed reception.

Despite some of the concerns with the administration’s economic policies, the Korean economy has been performing well under Moon so far. Even with last week’s drop, the KOSPI is up over 4 percent since May 8. GDP in the second quarter is up 0.6 percent from the first quarter and the BOK has raised its growth forecast for the year from 2.6 percent to 3 percent. Yet, much of this can be attributed to increased exports rather than domestic demand. It will still take time for Moon’s domestically-oriented reforms to be fully implemented, but they will be under greater scrutiny if exports slow down, which Moody’s predicts will occur in late September.

Gauging the effectiveness of J-nomics will take time, but President Moon has been quick to get it off the ground. The administration is certainly making the most of its vote of confidence from the public, but, as Moon’s critics would argue, public approval of a policy does not guarantee its success.

Kyle Ferrier is the Director of Academic Affairs and Research at the Korea Economic Institute of America. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Photo from the Republic of Korea’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.