The Peninsula

South Koreans Consider Nukes, But Japan Remains an Unknown Variable

Published November 21, 2017

Category: North Korea, South Korea

By Hwan Kang

Massive protests erupted in South Korea prior to President Donald Trump’s visit to South Korea organized by both opponents and supporters of the U.S. president. Of note, the Korean supporters of Trump called for the deployment of nuclear weapons in South Korea, even though it had already been ruled out by the United States. Those who opposed calls for nuclear weapons deployment in South Korea did so in the name of peace and denuclearization. As can be seen in this case, the nuclear armament issue has become the center of political conflicts in South Korea. Supporters of nuclear weapons on the Korean peninsula still relate the issue with President Trump despite his administration’s opposition because they identify politically with conservatives. Progressives oppose such calls from conservatives out of fear of potential nuclear war on the peninsula, in some cases extending the argument to demand termination of sanctions on North Korea and the withdrawal of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system.

Public Sentiment in South Korea over Tactical Nuclear Deployment

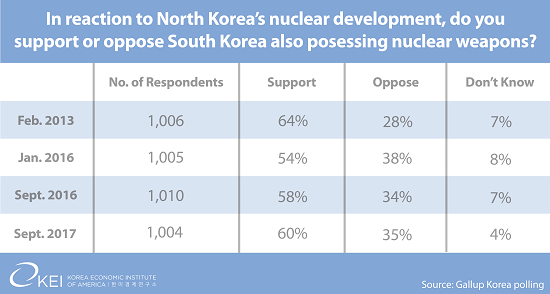

While such protests may portray the situation as a clash of equal political forces, the polls actually show a different picture when it comes to developing nuclear weapons in South Korea. According to Gallup Korea, when people were asked if they agreed with South Korea acquiring nuclear weapons after the 6th nuclear test by North Korea last September, 60 percent of the respondents agreed while 35 percent disagreed. In the past, when Gallup Korea conducted a poll on the same question after North Korea’s nuclear tests, the result mostly came out in favor of Korea acquiring nuclear weapons. Of course, such analysis can be seen as unrepresentative, as these numbers only represent public sentiment when tensions were high on the Korean Peninsula.

Similar survey results have come out in a poll done by Korea Society Opinion Institute (KSOI) concerning the issue of tactical nuclear deployment. The KSOI poll showed that 68.2 percent of the respondents answered that South Korea needs tactical nuclear deployment for defense against North Korea, while 25.4 percent answered that the country does not need deployment as “it will worsen South-North relations.” Conservative political leader Hong Jun-pyo uses this polling data as the basis for his petition campaign for tactical nuclear deployment, claiming to have gathered five million signatures in support. However, the same polling data has also indicated that 50.1 percent of the respondents prefer diplomatic means to denuclearize North Korea, while 47 percent preferred military actions. Therefore, it would be hasty to conclude based on this polling data that South Koreans want to quickly bring in or develop nuclear weapons, and more discussion among South Koreans would be needed before any action is taken.

Nuclear Arms in Korean Peninsula and Japan

Henry Kissinger recently commented that the call for the nuclear arming of South Korea to match North Korea may be a part of a trend towards more nuclear proliferation in East Asia. North Korea is certainly at fault for starting this concern. However, there is no guarantee that South Korea’s reaction to the predicament will not play an important role in influencing neighboring country’s behavior. If the call for nuclear armament in South Korea persists, whether through tactical deployment or domestic development, it may reinforce the already strong political rationale for Japan to follow suit – a fact that is very much on the minds of South Koreans after the successful reelection of Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who supports an expanded defense force in Japan. Additionally, Western media aggravates the sentiment by hinting that both countries have not yet ruled the nuclear development out in their future plans.

However, one of the biggest variables to consider in such a dismal proliferation scenario is Japan’s inherent fear of nuclear war, along with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) that both countries have signed. Japan has persistently opposed nuclear armament both in their country and on the Korean Peninsula. In a July 2017 joint poll done by Genro NPO on the North Korea military crisis and nuclear deployment in South Korea and Japan, 74 percent of Japanese respondent disagreed with the prospect of Japan acquiring nuclear weapons. The number almost matches the percentage of Koreans who disagree with the nuclear armament of Japan. It is actually the Koreans who have a strong inclination towards acquiring nuclear weapon inside their own country, according to the same poll. Nearly 70 percent of Koreans answered that they agree with possession of nuclear weapons in South Korea, while 80 percent of the Japanese disagreed with the idea.

Of course, to get a more accurate glimpse of South Korean sentiments while considering the Japan variable, it is important to ask additional questions such as “would you still agree to the development of nuclear weapons in South Korea if it meant Japan would also acquire nuclear weapons?” The question is frequently raised by various media and experts, some considering it as a valid worry that will concern Koreans, while others argue that Japan would understand the predicament and not go nuclear.

Such ramifications illustrate that the deployment of nuclear weapons in South Korea is not simply a question of deterrence against North Korea as some might want to believe. There should also be more frequent polling to gauge evolving public opinion on the issue, as the public may not have taken into account major events such as President Moon’s full explanation regarding his disapproval of deploying nuclear weapons in South Korea after the above-mentioned polls were being conducted. As a result, South Korea should not act rashly the name of security because its decision and potential consequences will not be confined only within its borders.

Hwan Kang is currently an Intern at the Korea Economic Institute of America as part of the Asan Academy Fellowship Program. He is also a student of Seoul National University in South Korea. The views expressed here are the author’s alone.

Image from Luke Shin’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.